Parco Gallery is one of those places that, if it didn’t exist, would need to be invented. Founded in 2018 by Loredana Bontempi and Emanuele Bonetti, it was created as an experimental space linked to contemporary visual culture, with a particular focus on graphic and editorial design. The history of the gallery is closely linked to the journey of the studio, which was founded by the same Loredana and Emanuele in 2010. The synergy between the two entities, which are two faces of the same coin, makes Parco a place of meeting and contamination between disciplines, in which to explore new design dimensions.

The latest activation of the space, on which our investigation opens, revolves around the multifaceted figure of Patrick Thomas, a Berlin-based graphic designer and artist, for the first time in Italy. His exhibition, In Situ, is a visual production of unexpected materials and formats, generated in the gallery from research on the urban context.

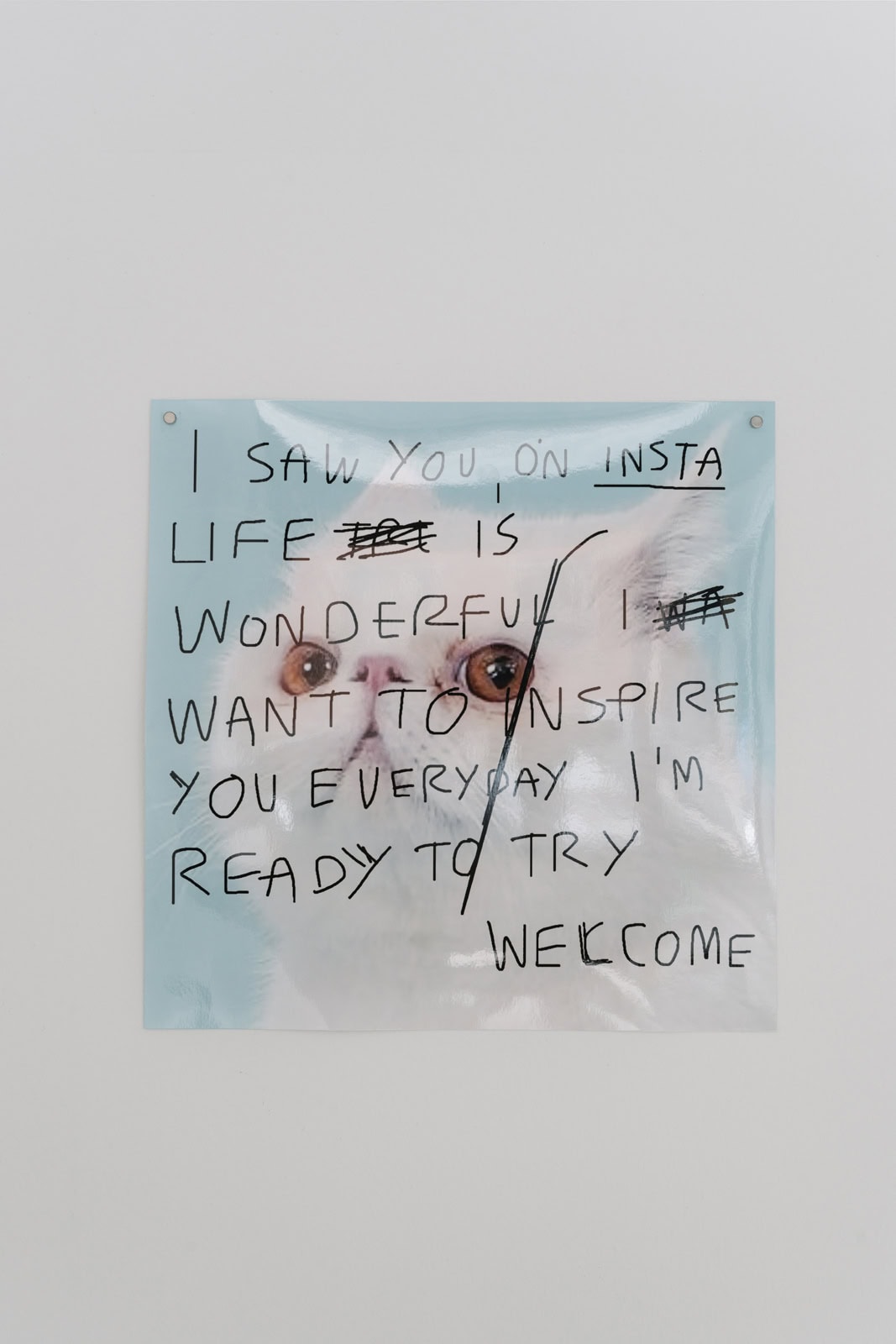

Much of the work was carried out by the artist directly in Parco spaces, transforming provisional elements into permanent structures. There is also a pre-existing series, brought by Thomas to the gallery to complete the installation. It is a reflection on social networks, and on our identities that dissolve in the vastness of the web. “Me!” we all seem to shout, in fear of disappearing. Yet it is our very presence there that deprives us of a piece of ourselves. Are social media really ruining our lives, or are they just transforming them into something never seen before? I asked Loredana and Emanuele, who told me what brought them here, but also in which direction they are now going.

Robin Sara Stauder: What needs does the gallery arise from? How does it relate to the studio?

Parco Gallery: The gallery arises from the need to have—first of all ourselves—a space for research and discussion. Initially to broaden the discourse on graphic design, which all too often tends to look to the past and within national boundaries, and to bring to Milan a series of experiences that are particularly relevant to us. In the first two years of the gallery, we hosted designers from the Netherlands, England, Germany, Romania, and the Czech Republic, some of whom had never been hosted in Italy, none outside academic contexts. 2020 inevitably shuffled the cards, not only making it more difficult to collaborate abroad but also reawakening the need to dialogue with the local scene. The fundamental need has always been to have a place for exchange with those who design contemporary visual culture and those who experience it, to confront each other on both conceptual and extremely pragmatic themes, constantly feeding our desire to learn. Having the opportunity to know similar realities to ours in such depth has helped us understand and appreciate the differences in approach and paradoxically has helped us better understand our identity as a studio.

RSS: What is your vision as curators? What are your goals?

PG: Our goal is to promote the culture of graphic design, which still today, in Italy, lives in the shadow of disciplines considered nobler, such as fashion and product design. How many people, when hearing the word design, think of an Albe Steiner poster? How many think of a Starck juicer? To promote it within the community of professionals, inevitably giving our personal interpretation of graphic design, the same one that we apply daily in the work of the studio: form is a means—essential and incredibly fascinating—at the service of content, never an end. But what happens when that form is free to express itself from the constraints imposed by the economic context? But also to promote it within a more generalist audience, the one that passes in front of our windows, who may be curious and fascinated by what happens inside and try to get in touch.

RSS: What is the common thread among the exhibitions you curate? What are the most important themes to you?

PG: The common thread of the Parco Gallery exhibitions could be freedom. The possibility of experimenting and trying outside of a commission, the opportunity to reflect on the role of the graphic designer in contemporary society, but also on graphics and its relationship with human beings. How many and what forms can it take? How does it influence our emotions? We opened the gallery with a collection of our references, stacks of paper materials collected during years of travel and kept as visual reminders, and we were amazed to discover that after years the value of those objects was no longer only related to a colour or a typographic character, but to the memory of a moment. We hosted Radim Pesko, who, through the introduction of a special glyph—the interfinity mark—questions the logic with which we ask questions without an answer, Giosampietro, whose production of graphic artefacts is almost accidental, within a process aimed at the production of objects, and destined to be lost up to Patrick Thomas, whose collages are a way to deepen and crystallize the visual culture of the place where the exhibition takes place.

RSS: To use your words: “What do you mean by beauty?”

PG: Obviously, we don’t have an answer to this question. Beauty is something that can surprise us, capture us, keep us still and move us. We believe that beauty is the engine of the human soul. What else moves us so strongly? Phidias and John Cage, harmony, disharmony, composition, music, and colour, in the end, are all emotions. We believe that beauty is what we should aspire to as a species. A full and shared beauty. Not just formal.

RSS: What does Patrick Thomas represent in the contemporary landscape? And for you?

PG: Patrick has been able to ride his ideals, leaving behind everything that the profession of graphic designer at the service of super consumption carries with it. As a graphic artist, he manages to lay bare the visual and conceptual values of images, leaving out the dynamics of clients and products. He is able to involve students and non-professionals, and immerse them in a world of expressive and timeless basic design.

RSS: One of the QR codes that can be framed during the exhibition leads to a landing page that reads the following message, taken from Jaron Lanier’s work: “Social media is ruining your life”. As communication designers, how do you approach this debate? Do you think it is possible to outline a new paradigm?

PG: We often ask ourselves, “What designers would we be without social networks?” We don’t have certain answers, but many questions that often lead us to seek alternative paths to those proposed on social media. The most visual social network is obviously Instagram, and for this reason, we feel it is the most cumbersome in our profession. One of the reasons the gallery was born is also to go beyond this mode of experiencing graphic images that travel on the surface. We felt the need to go beyond the impact of 8 seconds of attention, both as users and creators of images. For this reason, our format consists not only of images on display but also of vertical dives, books, meetings and stories between people.

RSS: “The formative influence of detritus” seems like a declaration of love for situationist détournement. What is the formative and design value of “drift”?

PG: No more bad vibes. For Parco Gallery to function, it is necessary that those who accept to exhibit with us inside our space are open to dialogue and willing to collaborate. We have been fortunate to collaborate with people who fully embraced the project, investing personally more than we could have ever asked for. This type of dedication is essential to keep the desire alive and to move forward. No more compromises. If dialogue, confrontation, and even conflict in some ways are an integral part of our way of designing and are the basis of the gallery’s activity, there are topics that we are no longer willing to negotiate. Equality, sustainability, and social responsibility. Ethical and value-based issues on which we believe we must take a stand as professionals and as people. We are aware that everything is destined to end, beautiful things as well as bad things. We hope that our passion and our desire to learn will last as long as possible – so far they have certainly been the two things that have consistently fueled our projects – and continue to push us into new experiences. Everything that ends does so to make way for something new, which is why we hope that when this experience ends, it has left a significant mark. As Manuel Agnelli (but also Schopenhauer) would say, there is nothing that lasts forever.